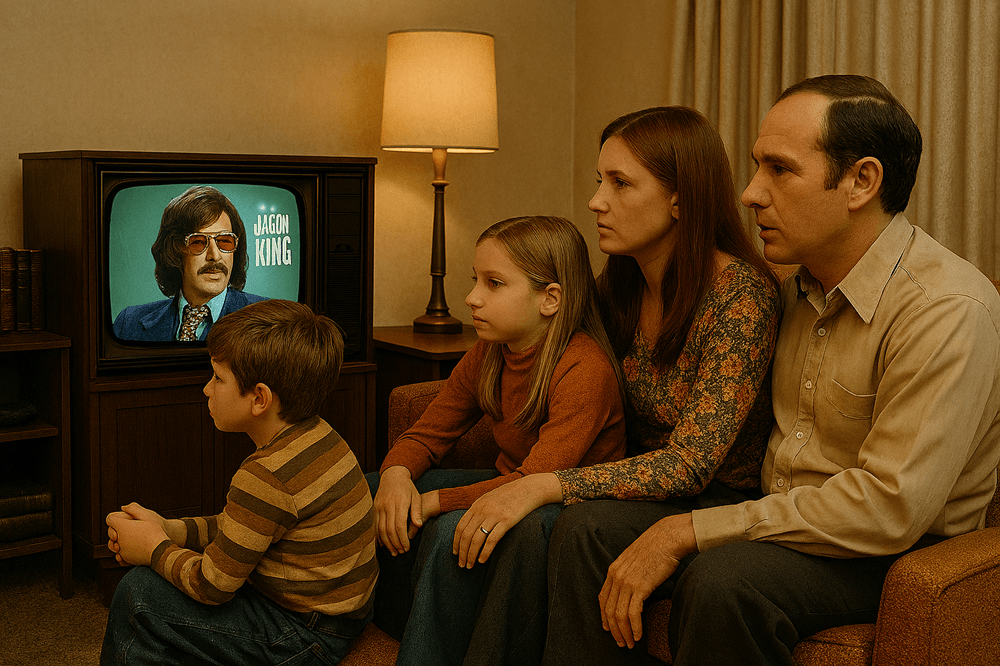

If you listen to my podcast Very British Futures than chances are you know about I Don’t Do Sci-Fi, the podcast produced by good friends of mine. This Christmas, Kevin Hiley and Rebecca Wray produced a two-hour special episode for YouTube featuring clips from Dani Wray’s least favourite decade – The Seventies. Joining her and Rebecca to watch this smorgasbord of vintage television was myself and John Isles.

Despite the title of their podcast, the one genre this night did not cover was science fiction. Instead we commented on a wide range of mainstream, mostly peak-time television, interspersed with period adverts. It was a fun night and the team have tracked down some fascinating moments of pop culture. From farming soap Emmerdale, to a music special from Lena Zavaroni and Bonnie Langford, to period drama Affairs of the Heart, to the classic Blue Peter lineup of Purves, Noakes and Singleton and much more. I hope our commentary is as entertaining if you watch it.

More from their website: “There are lots of common phobias: Heights, snakes, spiders, Mr Tumble. Regular listeners of the podcast will know that Dani has a phobia of a whole decade! Her face scrunches up in uncontrollable disgust whenever films and TV from the 1970s come up! So for this festive episode, we’ve sat her down (contrary to popular belief, body restraints were mostly unnecessary) to watch a bumper selection of 1970s British television!

“We wanted Dani to have an authentic, ordinary 1970s viewing experience so instead we’re watching chunks of soap operas, sit-coms, prestige drama, variety shows, science programmes, adverts, and more! So come with us back to that distant land of monster sideburns, flares, polluting cars, three day weeks, casual sexism, and a whole lot of brown! Joining Dani, Rebecca and John for this holiday special is returning guest Gareth Preston, who actually lived through the 1970s, and almost came out of it sane!”

Watch it on YouTube now!