One of the hazards of nostalgia for old children’s television is that fans sometimes forget they’ve done a lot of maturing since they watched their favourite programmes as youngsters. It became a problem for Terrahawks, Gerry Anderson’s comeback to puppet adventures in the Eighties, only to face criticisms from the viewers who’d grown up on Thunderbirds in the Sixties who found these new stringless stories somewhat lacking. Nevertheless plenty of their children did enjoy it, and not just in the UK but in countries such as the United States and Japan too.

Terrahawks could be the strangest, boldest, most Eighties Anderson show you’ve (probably) never seen. If you grew up on Thunderbirds, Captain Scarlet, or Space: 1999, you might think you know what to expect from a Gerry Anderson production: sleek vehicles, heroic pilots, and a tone that balances earnestness with spectacle. But in 1983, Anderson and script editor Tony Barwick created was something far stranger, cheekier, and more anarchic than anything that came before.

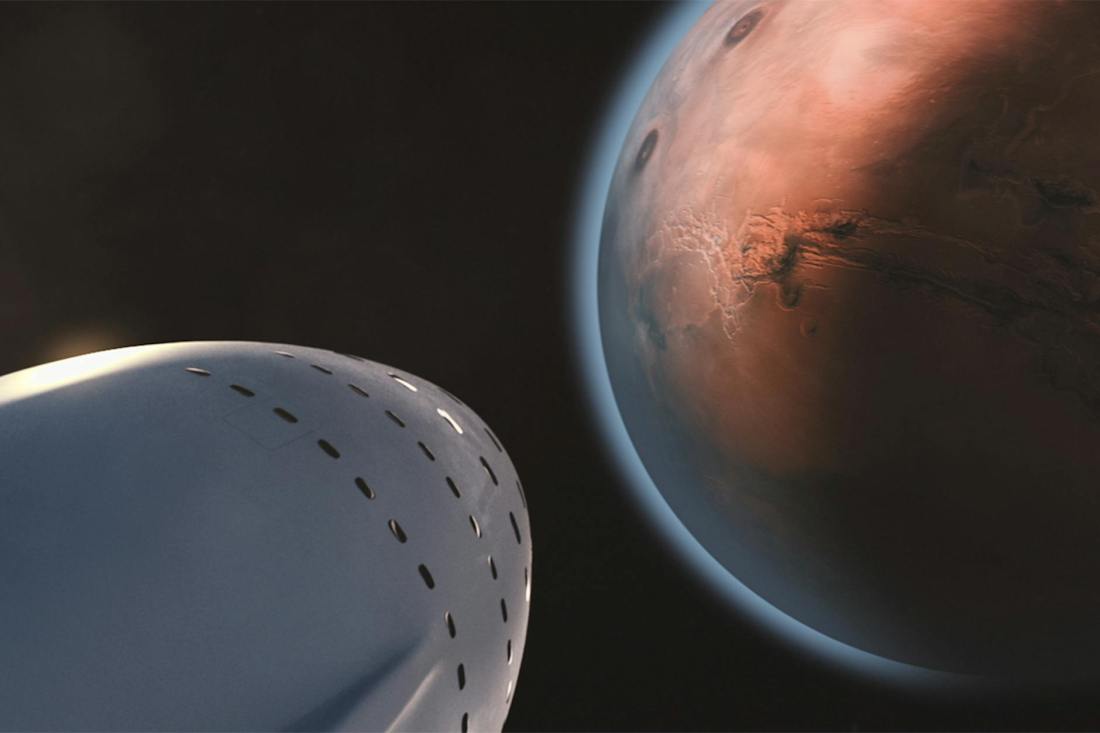

Terrahawks is a British science‑fiction series created by Gerry Anderson and Christopher Burr, originally airing on ITV from 1983 to 1986. It marked Anderson’s first new puppet‑driven show since the 1960s, but this time he ditched the iconic Supermarionation look for a new technique dubbed “Supermacromation”— hand and rod puppets more akin to The Muppets or Spitting Image giving the characters a rubbery, cartoonish energy.

Set in the year 2020, the series follows an elite defence force—the Terrahawks—as they protect Earth from a bizarre and theatrical Martian menace led by Zelda, an android witch with a cackling laugh and a flair for psychological warfare. Rumour has it that Anderson encouraged the sculptor to base her face on his ex-wife Sylvia. Her monstrous creations, from cube‑headed robots to grotesque alien offspring, gave the show a surreal edge that set it apart from Anderson’s earlier, more polished worlds.

Even among Anderson’s eclectic catalogue, Terrahawks is an oddity. It mixes slapstick humour with genuine peril, Saturday‑morning colour with unsettling villain designs, and high‑concept sci‑fi with eccentricity only British television could produce.

A few things that make it uniquely memorable are Zelda and her brood – Some of the most distinctive antagonists in Anderson’s universe, equal parts creepy and comedic. The Zeroids – Spherical robot soldiers whose bickering and bravery became a highlight of the show. A playful tone – Less stiff than Thunderbirds, less grim than Captain Scarlet, and far more willing to be weird. Inventive model work – Even with a smaller budget than Anderson’s 60s heyday, the effects team delivered imaginative vehicles and miniature action sequences.

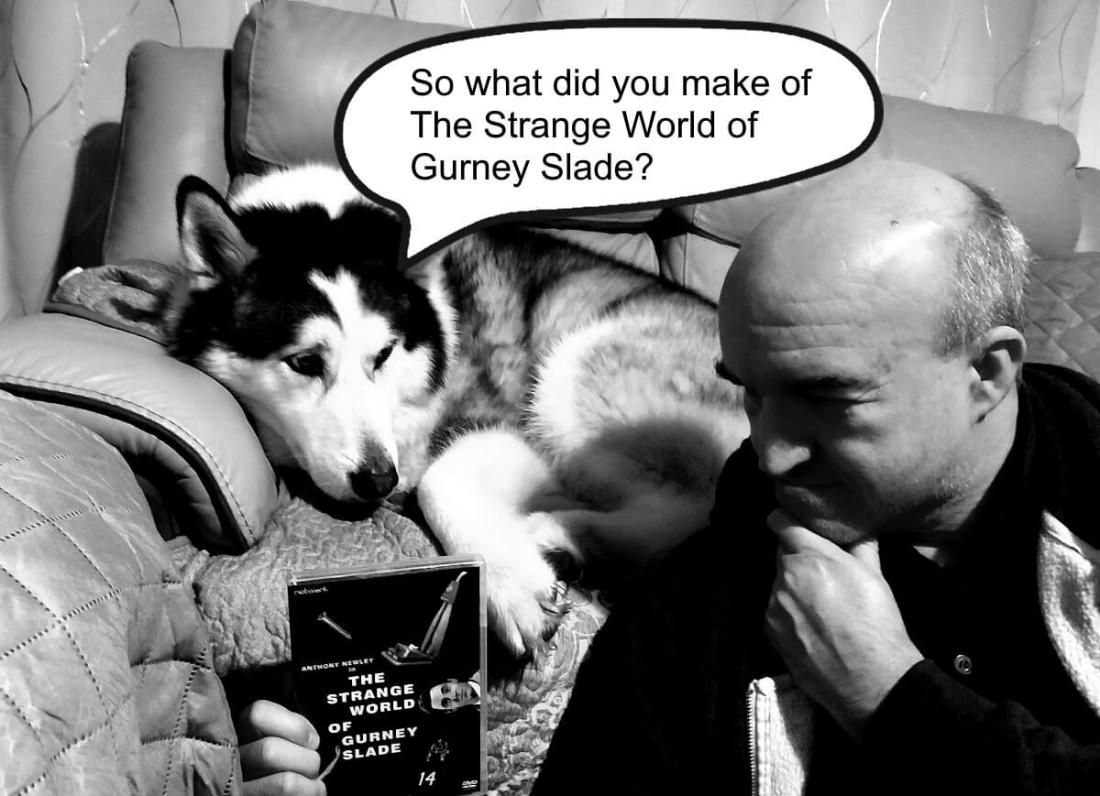

On the Very British Futures podcast, we love exploring the corners of British sci‑fi that deserve a second look—or a first one for the uninitiated. Terrahawks is a perfect fit: ambitious, eccentric, and bursting with ideas that reflect both the legacy of Anderson’s earlier work and the experimental spirit of 1980s television.

In our episode, we dive into why its tone is so different from his 60s classics, the show’s most memorable characters and episodes, and its cult legacy and why it still sparks debate among fans.

You can listen to the episode on Spotify and other major podcast platforms.

Whether you’re nostalgic for the original broadcasts or discovering the series for the first time, the episode offers a fresh, affectionate, and occasionally cheeky look at this odd slice of British sci‑fi history. I was lucky to be joined by regular guest Andrew Roe-Crines and Ken Moss from the Extonmoss Experiment podcast. We’re the perfect companions to your viewing, and Very British Futures is right there to guide you through the model scale madness.